Hormonal changes

Increasing levels of estradiol and progesterone and the placental hormones, HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) drive many of the pregnancy related endocrine and metabolic changes

- Estradiol—appears to stimulate lactotrophs in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland. These may triple in size to prepare breast for lactation

- Posterior Pituitary glands—store oxytocin an antidiuretic hormone ADH. HCG resets the receptors for thirst and ADH release—leads to decrease in serum sodium concentration and polyuria (in some women)

- Thyroid gland—remains normal in size—but the effects of estrogen on thyroxine-binding globulin and the stimulation of the thyrotropin TSH receptor by HCG lead to fluctuations in free T4 and T3 levels and in TSH, usually within normal range

- Placenta hormones—contribute to increase insulin resistance in later pregnancy abd shift from carbohydrate to fat metabolism

- End of pregnancy—increasing in placental corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) produce a state of relative hypercortisolism that may be a trigger for labor

- Progesterone levels increase leading to increase tidal volume and minute ventilation increase—leads to dyspnea. It also relaxes tone and contractions in the ureters, causing hydronephrosis. In the bladder there is increased risk for bacteriuria

- Progesterone and estradiol lower esophageal sphincter tone—reflux and heartburn

- Cardiovascular changes are significant—erythrocyte mass and plasma volume increase (hemodilution and physiologic anemia). Cardiac output increase, systemic vascular resistance and BP fall.

- Musculoskeletal changes—from weight gain and relaxin, lumbar lordosis (low back pain); ligamentous laxity in the sacroiliac joints and the pubic symphysis, to ease passage of the baby through the birth canal

Physical Changes in Pregnancy

- Breasts–There may be tenderness and tingling in the breasts that makes them more sensitive during examination. By the third month of gestation, the breasts become more nodular, requiring careful palpation to avoid discomfort as you examine for any breast masses.

- Nipples–become larger and more erectile. From mid to late pregnancy, colostrum, a thick, yellowish secretion rich in nutrients, may be expressed from the nipples. The areolae darken, and Montgomery’s glands are more prominent. The venous pattern over the breasts becomes increasingly visible as pregnancy progresses.

The early diagnosis of pregnancy is based in part on changes in the vagina and the uterus.

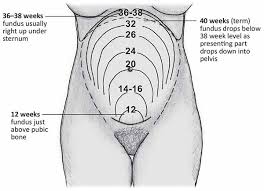

- Uterus– The abdomen’s most notable change is distention, primarily from the increasing size of the growing uterus and fetus. Early distention from fluid retention and relaxation of abdominal muscles may be noted before the uterus becomes an abdominal organ (12–14 weeks of gestation).

The uterus is the organ most affected by pregnancy. Early in pregnancy, it loses the firmness and resistance of the nonpregnant organ. The palpable softening at the isthmus, called Hegar’s sign, is an early diagnostic sign of pregnancy and is illustrated on the right.

Over the course of 9 months, the uterus increases in both weight and size. Its weight grows from 50-70gm to 800-1200gm, and its volume expands from 10ml to 5Liters.

As the uterus grows, it changes shape and position. The nongravid uterus may be anteverted, retroverted, or retroflexed. Up to 12 weeks of gestation, the gravid uterus is still a pelvic organ. Regardless of its initial positioning, the enlarging uterus becomes anteverted and quickly fills space usually occupied by the bladder, triggering frequent voiding. By 12 weeks’ gestation, the uterus straightens and rises out of the pelvis and can be felt when palpating the abdomen.

The enlarging uterus pushes the intestinal contents laterally and superiorly and stretches its supporting ligaments, sometimes causing pain in the lower quadrants. It adapts to fetal growth and positions and tends to rotate to the right to accommodate to the rectosigmoid structures in the left side of the pelvis.

- Vagina—with the increased vascularity throughout the pelvic region, the vagina takes on a bluish or violet color. The vaginal walls appear thicker and deeply rugated because of increased thickness of the mucosa, loosening of the connective tissue, and hypertrophy of smooth muscle cells. Vaginal secretions are thick, white, and more profuse. Vaginal pH becomes more acidic due to the action of Lactobacillus acidophilus on the increased levels of glycogen stored in the vaginal epithelium. This change in pH helps protect the woman against some vaginal infections, but increased glycogen may contribute to higher rates of vaginal candidiasis.

- Cervix and Ovaries— The cervix also looks and feels quite different. Pronounced softening and cyanosis appear very early after conception and continue throughout pregnancy (Chadwick’s sign). The cervical canal is filled with a tenacious mucous plug that protects the developing fetus from infection. Red, velvety mucosa (cervical erosion or eversion) around the os is common on the cervix during pregnancy and is considered normal.

The ovaries and fallopian tubes undergo changes as well, but few are noticeable during physical examination. Early in pregnancy, the corpus luteum, the ovarian follicle that has discharged its ovum, may be sufficiently prominent to be felt on the affected ovary as a small nodule, but it disappears by midpregnancy. It is important to examine the fallopian tubes to rule out a tubal pregnancy.

- Abdomen—growing abdomen may produce purple The linea nigra, a brownish black pigmented line following the midline of the abdomen, may become evident. The rectus abdominis muscles may separate at the midline—diastasis recti

History

The common concerns

- Symptoms of pregnancy

- Maternal attitudes about pregnancy

- Current health: smoking, alcohol, use of illicit drugs, domestic violence

- Prior complication of pregnancy

- Chronic illnesses and family history

- Determining week of gestation by date and expected date of delivery

3 Goals of the initial prenatal visit

- Confirm the pregnancy

- Assessing the health status of the mother and any risks for complications

- Counseling to ensure birth of a healthy baby

- Ask about symptoms of pregnancy; explain that urine testing for beta HCG offers the best confirmation of pregnancy (blood serum rarely needed for confirmation)

- Ask about the mother’s concerns and attitudes about the pregnancy (support, fears, and concerns)

- Assess the current state of health and any risk factors that could adversely affect the mother or fetus or cause any complications.

- Assess the past obstetric history

- Ask about the past medical history (HTN, DM, cardiac, asthma, SLE, seizures, STD, exposure to diethylstilbestrol in utero, or HIV)

- Review any family history of chronic illness or genetically transmitted diseases (sickle cell, cystic fibrosis, or MS)

Weeks of Gestation and Expected Date of Delivery

- Count Expected weeks of gestation by:

- Menstrual Age: count in weeks from either the first day of the LMP (most used)

- The weeks of gestation at the time of examination tell you the expected size of the uterus if the LMP was normal, the dates were remembered accurately, and conception actually occurred

- You can then compare the expected size by dates with what you actually palpate during the bimanual examination, or abdominally, if pregnancy is beyond 14 weeks of gestation.

- Conception age: the date of conception

- Menstrual Age: count in weeks from either the first day of the LMP (most used)

- Count Expected Date of Delivery by:

- The first day of LMP is used to determine the EDD (if regular menstrual cycle 28-30d).

- Naegele’s rule: Add 7 days to the first day of LMP, then Subtract 3 months, and add 1 year.

- If pt cannot remember LMP or irregular cycles then determine dates by US in first trimester

- Establish the desired frequency of follow up visits based on the patient’s needs.

Health Promotion

Important topics for health promotion

Nutrition

Weight gain

Exercise

Smoking, alcohol, and illicit drugs

Screening for domestic violence

Immunizations

Nutrition

Counseling about nutrition and exercise is important to the health of the pregnant woman and baby. Evaluate the nutritional status of the woman at the first prenatal visit, including a diet history, measurement of height and weight, and screening for anemia by checking the hematocrit. Be sure to explore the woman’s habits and attitudes about eating and weight gain, as well as her use of needed vitamin and mineral supplements.

- Develop a nutrition plan that is appropriate to the woman’s cultural preferences. Be sure there is a balanced increase in calories and protein, since protein will be used for energy, rather than growth, unless sufficient calories are consumed.

- Increase Diet by: 300kilocalories; 5-10 grams of protein; 15 milligrams of iron; 250 milligrams of calcium; and 400-800micrograms of folic acid

- Prescribe a multivitamin with 400micrograms of folic acid a day

- Caution with: unpasteurized dairy, undercooked meats, seafood (controversial), mercury (shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and canned albacore tuna)

Weight Gain

Ideal weight gain during pregnancy follows a pattern: very little gain the first trimester, rapid increase in the second, and a mild slowing of the increase in the third trimester. Women should be weighed at each visit, with the results plotted on a graph for the woman and health care provider to review and discuss.

- Average weight gain is 28lbs or 10Kg

Exercise

The 2002 guidelines of American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology suggest 30min a day of moderate exercise. Women who exercised before can continue mild to moderate exercise 30min 3 days a week, those who have not exercise should be more cautious and consider program developed for pregnant women.

- Avoid supine exercise after 1st trimester

- Stop when feels fatigued or uncomfortable or overheated

- No exercise that causes loss of balance or contact sports in 3rd trimester

Smoking, Alcohol, or illicit drugs

- No smoking—linked to complications of labor (placental abruption and placenta previa, and preterm births, low birth weight, and perinatal death)

- Women with addictions to alcohol or drugs should be referred for treatment (neurodevelopmental outcomes)

Screen for domestic violence

- More likely to be abused by an intimate partner or when patterns of abuse intensify, increasing the risk for delayed prenatal care, miscarriage, and low birth weight

- Prevalence is from 7-20% and may result in femicide or death to mother and baby

- Clues include: frequent changes in appointments at last min, behavior during the interview, chronic HA or abd pain, and bruises or other signs of injury

- Offer information to those abused (shelters, counseling, hotlines); assess safety and make referrals

- National Domestic Violence Hotline. Website. 1-800-799-SAFE (7233); TTY for hearing impaired (1-800-787-3224)

Immunizations

- Review the patients history

- All should be up to date (FLU and Tetanus)—can be administered in any trimester

- If indicated pneumococcal, meningococcal, and hep B are safe in pregnancy

Pregnant female Exam

If you have not met the woman before, taking the history before asking her to gown shows respect for her right to be treated with dignity. Ask the woman to put on the gown with the opening in front to ease the examination of both the breasts and the pregnant abdomen.

Positioning

- The semi-sitting position with the knees bent affords the greatest comfort, as well as protection from the negative effects of the weight of the gravid uterus on abdominal organs and vessels.

- Prolonged periods of lying on the back should be avoided because the uterus then lies directly on the woman’s vertebral column and may compress the descending aorta and inferior vena cava, interfering with return of venous blood from the lower extremities and the pelvic vessels.

- Encourage the woman to sit again briefly before proceeding to the pelvic evaluation. All other examination procedures should be done in the sitting or left-side–lying position.

- Supine hypotension syndrome after 20 weeks is a severe form of this diminished circulation and may lead the woman to feel dizzy and faint, especially when lying down.

Equipment

The examiner’s hands are the primary “equipment” for exam; they should be warm and firm yet gentle in palpation, the fingers should be together and flat against the abdominal or pelvic tissue to minimize discomfort, and should be done with smooth continuous contact against the skin rather than kneading or abrupt motion.

- The more sensitive palmar surfaces of the ends of the fingers yield the greatest amount of information.

- The gynecologic speculum is used for inspecting the cervix and the vagina a speculum of larger than expected size may be needed.

- The cervical brush is not recommended for Pap smears in pregnant women because it often causes bleeding. The Ayre wooden spatula and/or cotton- tipped applicator is appropriate.

General Inspection

Inspect the overall health, nutritional status, neuromuscular coordination, and emotional state as the woman walks into the exam room and climbs on the examination table. Discussion of the woman’s priorities for the examination, her responses to pregnancy, and her general health provide useful in- formation and help to put the woman at ease.

Vital Signs, Height, and Weight

Blood Pressure– Take a baseline reading helps to determine the woman’s usual range.

- In midpregnancy, blood pressure is normally lower than in the nonpregnant state.

- Gestational HTN is systolic BP ≥140 and diastolic BP ≥90, first occurring after week 20 and without proteinuria

- Chronic HTN is systolic BP ≥140 and diastolic BP ≥90 before pregnancy, before week 20, and after 12 weeks postpartum

- Preeclampsia is systolic BP ≥140 and diastolic BP ≥90 after week 20 and with proteinuria

Height & Weight—Calculate BMI (19-25 normal standards for prepregnant state)

- First-trimester weight loss related to nausea and vomiting is common but should not exceed 5 % of prepartum weight

- Weight loss of more than 5 % during the first trimester may be due to excessive vomiting or hyperemesis.

Head and Neck

Stand facing the seated woman and observe the head and neck, including the following features:

- Face— The mask of pregnancy, chloasma, is normal. It consists of irregular brownish patches around the eyes or across the bridge of the nose.

- Facial edema after 24 weeks of gestation suggests PIH (pregnancy induced HTN).

- Hair—including texture, moisture, and distribution. Dryness, oiliness, and sometimes minor generalized hair loss may be noted.

- Localized patches of hair loss should not be attributed to pregnancy, but common after

- Eyes—Note the conjunctival color.

- Anemia of pregnancy may cause pallor.

- Nose—including the mucous membranes and the septum. Nasal congestion is common during pregnancy.

- Nosebleeds are more common during pregnancy. Nasal septum can show signs of cocaine use may be present.

- Mouth— especially the gums and teeth.

- Gingival enlargement with bleeding is common during pregnancy.

- Thyroid gland—Inspect and palpate the gland. Symmetric enlargement is expected.

- Marked or asymmetric enlargement is not due to pregnancy and should be investigated

Thorax and Lungs

- Inspect the thorax for the pattern of breathing.

- Elevation of diaphragm ad increased chest diameter in first trimester

- Tidal volume and alveolar minute ventilation increases, but RR remains constant

- Expect respiratory alkalosis

- Pursue complaints off dyspnea accompanied by cough or respiratory distress for possible infection, asthma, or pulmonary embolus

Heart

- Palpate the apical impulse. In advanced pregnancy, it may be slightly higher than normal 4th I intercostal space, because of transverse and leftward rotation of the heart from the higher diaphragm.

- Auscultate the heart. Soft, blowing murmurs (venous hum and systolic or continuous mammary soufflé) are common during pregnancy, reflecting increased blood flow in normal vessels.

- Mammary soufflé can be heard late in pregnancy and during lactation (2nd or 3rd interspace)

- Murmurs may accompany anemia. New diastolic murmurs and dyspnea with exertion should be investigated

Breasts

- Inspect the breasts and nipples— for symmetry and color. The venous pattern may be marked, the nipples and areolae are dark, and Montgomery’s glands are prominent.

- An inverted nipple needs attention if breast-feeding is planned.

- Palpate for masses— During pregnancy, breasts are tender and nodular.

- A pathologic mass may be difficult to isolate.

- Compress each nipple—between your index finger and thumb. This maneuver may express colostrum from the nipples.

- A bloody or purulent discharge should not be attributed to pregnancy.

Abdomen

- Position the pregnant woman in a semi-sitting position with her knees flexed.

- Inspect any scars or striae, the shape and contour of the abdomen, and the fundal height. Purplish striae and linea nigra are normal in pregnancy. The shape and contour may indicate pregnancy size.

- Scars may confirm the type of prior surgery, especially cesarean section.

Palpate the abdomen for:

- Organs or masses— The mass of pregnancy is expected.

- Fetal movements.—These can usually be felt by the examiner after 24 weeks (and by the mother at 18–20 weeks).

- If movements cannot be felt after 24 weeks, consider error in calculating gestation, fetal death or morbidity, or false pregnancy.

- Uterine contractility— The uterus contracts irregularly after 12 weeks and often in response to palpation during the third trimester. The abdomen then feels tense or firm to the examiner, and it is difficult to feel fetal parts. If the hand is left resting on the fundal portion of the uterus, the fingers will sense the relaxation of the uterine muscle.

- Prior to 37 weeks, regular uterine contractions with or without pain or bleeding are abnormal, suggesting preterm labor.

Measure the fundal height—using a tape measure if the woman is more than 20 weeks’ pregnant. Holding the tape and following the midline of the abdomen, measure from the top of the symphysis pubis to the top of the uterine fundus. After 20 weeks, measurement in centimeters should roughly equal the weeks of gestation. For estimating fetal height between 12 and 20 weeks.

- If fundal height is more than 4 cm higher than expected, consider multiple gestation, a big baby, extra amniotic fluid, or uterine leiomyoma. If it is lower than expected by more than 4 cm, consider missed abortion, transverse lie, growth retardation, or false pregnancy.

Auscultate the fetal heart, noting its rate (FHR), location, and rhythm.

- Doptone— with which the FHR is audible after 10 weeks

- Fetoscope— with which it is audible after 18 weeks.

- Lack of an audible fetal heart may indicate pregnancy of fewer weeks than expected, fetal demise, or false pregnancy.

- The location of the audible FHR is in the midline of the lower abdomen from 12 to 18 weeks of gestation.

- After 28 weeks, the fetal heart is heard best over the fetal back or chest.

- The location of the FHR then depends on how the fetus is positioned. Palpating the fetal head and back helps you identify where to listen. (See Modified Leopold’s Maneuvers, pp. 888-890.)

- After 24 weeks, auscultation of more than one FHR with varying rates in different locations suggests more than one fetus

- If the fetus is head down with the back on the woman’s left side, the FHR is heard best in the lower left quadrant.

- If the fetal head is under the xiphoid process (breech presentation) with the back on the right, the FHR is heard in the upper right quadrant.

- The rate—is usually in the 160s during early pregnancy, and then slows to the 120s to 140s near term. After 32 to 34 weeks, the FHR should increase with fetal movement.

- An FHR that drops noticeably near term with fetal movement could indicate poor placental circulation or decreased amniotic fluid volume

- Rhythm— becomes important in the third trimester. Expect a variance of 10 to 15 beats per minute (BPM) over 1 to 2 minutes.

- Lack of beat-to-beat variability late in pregnancy warrants Investigation with an FHR monitor

Genitalia, Anus, and Rectum

- Inspect the external genitalia, noting the hair distribution, the color, and any scars. Parous relaxation of the introitus and noticeable enlargement of the labia and clitoris are normal. Scars from an episiotomy, a perineal incision to facilitate delivery of an infant, or from perineal lacerations may be present in multiparous women.

- Inspect the anus for hemorrhoids. If these are present, note their size and location.

- Palpate Bartholin’s and Skene’s glands. No discharge or tenderness should be present.

- Check for a cystocele or rectocele.

- Some women have labial varicosities that become tortuous and painful.

- Varicosities often engorge later in pregnancy. They may be painful and bleed.

- May be pronounced due to the muscle relaxation of pregnancy

Speculum Exam

- Inspect the cervix for color, shape, and healed lacerations. A parous cervix may look irregular because of lacerations.

- Take Pap smears and, if indicated, other vaginal or cervical specimens. The cervix may bleed more easily when touched due to the vasocongestion of pregnancy.

- Inspect the vaginal walls for color, discharge, rugae, and relaxation. A bluish or violet color, deep rugae, and an increased milky white discharge, leukorrhea, are normal.

- A pink cervix suggests a nonpregnant state.

- Vaginal infections are more common during pregnancy, and specimens may be needed for diagnosis.

- A pink vagina suggests a non- pregnant state. Vaginal irritation and itching with discharge suggest infection.

Bimanual Exam

- Insert two lubricated fingers into the introitus, palmar side down, with slight pressure downward on the perineum.

- Slide the fingers into the posterior vaginal vault. Maintaining downward pressure, gently turn the fingers palmar side up. Avoid the sensitive urethral structures at all times. With the relaxation of pregnancy, the bimanual examination is usually easier to accomplish. Tissues are soft and the vaginal walls usually close in on the examining fingers, giving the sensation of being immersed in a bowl of oatmeal. It may be difficult to distinguish the cervix at first because of its softer texture.

- Place your finger gently in the os, and then sweep it around the surface of the cervix. A nulliparous cervix should be closed, while a multiparous cervix may admit a fingertip through the external os. The internal os—the narrow pas- sage between the endocervical canal and the uterine cavity—should be closed in both situations. The surface of a normal multiparous cervix may feel irregular due to the healed lacerations from a previous birth.

- Estimate the length of the cervix by palpating the lateral surface of the cervix from the cervical tip to the lateral fornix. Prior to 34 to 36 weeks, the cervix should retain its normal length of about 1.5 to 2 cm.

- Palpate the uterus for size, shape, consistency, and position. These depend on the weeks of gestation. Early softening of the isthmus, Hegar’s sign, is characteristic of pregnancy. The uterus is shaped like an inverted pear until 8 weeks, with slight enlargement in the fundal portion. The uterus becomes globular by 10 to 12 weeks. Anteflexion or retroflexion is lost by 12 weeks, with the fundal portion measuring about 8 cm in diameter.

- With your internal fingers placed at either side of the cervix, palmar surfaces up- ward, gently lift the uterus toward the abdominal hand. Capture the fundal portion of the uterus between your two hands and gently estimate uterine size.

- Palpate the left and right adnexa. The corpus luteum may feel like a small nodule on the affected ovary during the first few weeks after conception. Late in pregnancy, adnexal masses may be difficult to feel.

- Palpate for pelvic muscle strength as you withdraw your examining fingers.

- A rectovaginal examination may be done if you need to confirm uterine size or the integrity of the rectovaginal septum. A pregnancy less than 10 weeks in a retroverted and retroflexed uterus lies totally in the posterior pelvis. Its size can be confirmed only by this examination.

- A shortened effaced cervix prior to 32 weeks may indicate preterm labor.

- An irregularly shaped uterus suggests uterine myomata or a bicornuate uterus, which has two distinct uterine cavities separated by a septum.

- Early in pregnancy, it is important to rule out a tubal (ectopic) pregnancy.

Extremities

- General inspection may be done with the woman seated or lying on her left side.

- Inspect the legs for varicose veins.

- Inspect the hands and legs for edema. Palpate for pretibial, ankle, and pedal edema. Edema is rated on a 0 to 4+ scale. Physiologic edema is more common in advanced pregnancy, during hot weather, and in women who stand a lot.

- Obtain knee and ankle reflexes.

- Varicose veins may begin or worsen during pregnancy.

Special Techniques

Modified Leopold’s Maneuvers

These maneuvers are important adjuncts to palpation of the pregnant abdomen beginning at 28 weeks of gestation. They help determine where the fetus is lying in relation to the woman’s back (longitudinal or transverse), what end of the fetus is presenting at the pelvic inlet (head or buttocks), where the fetal back is located, how far the presenting part of the fetus has descended into the maternal pelvis, and the estimated weight of the fetus. This information is necessary to assess the adequacy of fetal growth and the probability of successful vaginal birth.

- Common deviations include breech presentation (the fetal buttocks presenting at the outlet of the maternal pelvis) and absence of the presenting part well down into the maternal pelvis at term. Neither situation necessarily precludes vaginal birth. The most serious findings are a transverse lie close to term and slowed fetal growth that could represent intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR).

- First Maneuver (Upper Pole)

- Stand at the woman’s side facing her head.

- Keeping the fingers of both examining hands together, palpate gently with the fingertips to determine what part of the fetus is in the upper pole of the uterine fundus.

- Most commonly, the fetal but- tocks are at the upper pole. They feel firm but irregular, and less globular than the head. The fetal head feels firm, round, and smooth.

- Second Maneuver (Sides of the Maternal Abdomen)

- Place one hand on each side of the woman’s abdomen, aiming to capture the body of the fetus between them. Use one hand to steady the uterus and the other to palpate the fetus.

- The hand on the fetal back feels a smooth, firm surface the length of the hand (or longer) by 32 weeks of gestation. The hand on the fetal arms and legs feels irregular bumps, and also perhaps kicking if the fetus is awake and active.

- Third Maneuver (Lower Pole)

- Turn and face the woman’s feet.

- Using the flat palmar surfaces of the fingers of both hands and, at the start, touching the fingertips together, palpate the area just above the symphysis pubis.

- Note whether the hands diverge with downward pressure or stay together.

- This tells you whether or not the presenting part of the fetus, head or buttocks, is descending into the pelvic inlet.

- If the presenting fetal part is descending, palpate its texture and firmness.

- If not, gently move your hands up the lower abdomen and capture the presenting part between your hands.

- If the fetal head is presenting, the fingers feel a smooth, firm, rounded surface on both sides.

- If the hands diverge, the presenting part is descending into the pelvic inlet, as illustrated.

- If the hands stay together and you can gently depress the tissue over the bladder without touching the fetus, the presenting part is above your hands. The fetal head feels smooth, firm, and rounded; the buttocks, firm but irregular.

- Fourth Maneuver (Confirmation of the Presenting Part)

- With your dominant hand grasp the part of the fetus in the lower pole, and with your nondominant hand, the part of the fetus in the upper pole.

- With this maneuver, you may be able to distinguish between the head and the buttocks.

- Most commonly, the head is in the lower pole and the fetal buttocks are in the upper pole. If the head is above the pelvic inlet, it moves somewhat independently of the rest of the fetal body.

References

Dunphy, L.M., Winland-Brown, J. E. (2011). Primary Care: The Art and Science of Advanced Practice Nursing. (3rd ed). Philadelphia, PA. F.A. Davis

Uphold, C.R., & Graham, M.V. (2013). Clinical guidelines in family practice. (4th ed.) Gainesville, Fl.: Barmarrae Books, Inc.

Youngkin, E.Q., & Davis, M.S. (2012). Women’s health: A primary care clinical guide (4th. ed ). Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange.